The history of ‘coming out,’ from secret gay code to popular political protest.

You probably know what it means to “come out” as gay. You may even have heard the expression used in relation to other kinds of identity, such as being undocumented.

But do you know where the term comes from? Or that its meaning has changed over time?

In my new book, “Come Out, Come Out, Whoever You Are,” I explore the history of this term, from the earliest days of the gay rights movement, to today, when it has been adopted by other movements.

Selective sharing

In the late 19th and early 20th century, gay subculture thrived in many large American cities.

Gay men spoke of “coming out” into gay society – borrowing the term from debutante society, where elite young women came out into high society. A 1931 news article in the Baltimore Afro-American referred to “the coming out of new debutantes into homosexual society.” It was titled “1931 Debutantes Bow at Local ‘Pansy’ Ball.”

The 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s witnessed a growing backlash against this visible gay world. In response, gay life became more secretive.

Related | A Brief History of Gay Pirates in the Golden Age of Piracy

The Mattachine Society, the earliest important organization of what was known as the homophile movement – a precursor of the gay rights movement – took its name from mysterious medieval figures in masks. In this context, coming out meant acknowledging one’s sexual orientation to oneself and to other gay people. It did not mean revealing it to the world at large.

Such selective sharing relied on code phrases – such as “family,” “a club member,” “a friend of Dorothy’s,” “a friend of Mrs. King” or “gay” – that could be used in mixed company to designate someone as homosexual.

The term “gay” was originally borrowed from the slang of women prostitutes, when they used the word to refer to women in their profession. Of course, “gay” was ultimately “outed” when the gay rights movement adopted it following the Stonewall Rebellion in 1969.

Out in public

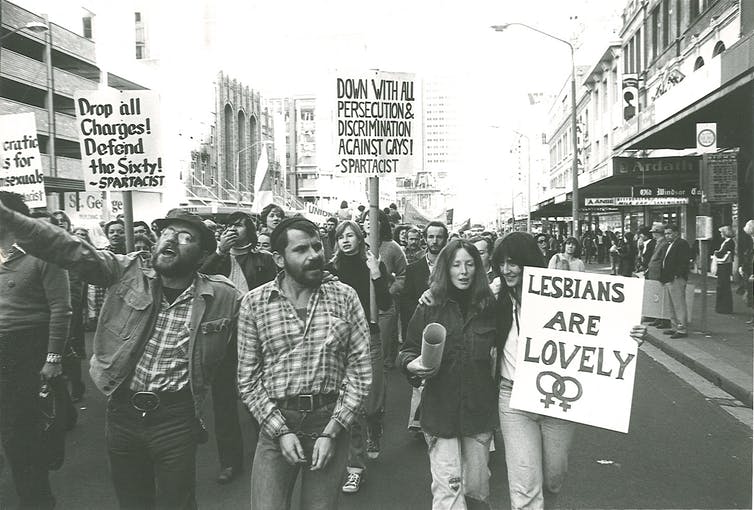

Coming out took on a more political meaning after the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, in which patrons of the Stonewall Inn in New York City fought back against a police raid. The rebellion included riots and a resistance that lasted for days. It was subsequently commemorated in an annual march known today as “gay pride.”

At the first Gay Liberation March in New York City in June 1970, one of the organizers stated that “we’ll never have the freedom and civil rights we deserve as human beings unless we stop hiding in closets and in the shelter of anonymity.”

Related | A Brief History of Manscaping

By this time, coming out was juxtaposed with being in the closet, conveying the shame associated with hiding. By the end of the 1960s, queer people who pretended to be heterosexual were said to be “in the closet” or labeled a “closet case” or, in the case of gay men, “closet queens.”

By the 1970s, mainstream journalists were already using the term beyond sexual orientation – to speak of, for instance, “closet conservatives” and “closet gourmets.”

A rite of passage

By presenting coming out as a way to end internalized self-hatred and achieve a better life, the LGBTQ movement helped to encourage people to come out, despite associated risks. It also showed how coming could be used to build solidarity and recruit other queer people.

For instance, in 1978, in his campaign to defeat a California initiative that would have banned gay teachers from working in state public schools, openly gay elected government official Harvey Milk urged people to “Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are.”

Related | The Long History of LGBT Video Game Characters

Milk gambled that if queer people told their friends they were gay, Californians would realize that they had friends, coworkers and family members who were gay and – out of solidarity – would oppose the proposition. The campaign helped defeat the initiative.

In the 1980s, the gay and lesbian rights movement radicalized in response to the Christian right and AIDS epidemic. Activists used the mantra “Come Out, Come Out, Wherever You Are” to demand that people declare their homosexuality. The coming out narrative became a rite of passage, something to be shared with others, and the centerpiece of gay liberation movements.

In your face

In the 1990s, the radical organization Queer Nation took coming out to a new level.

Its members wore T-shirts in Day-Glo colors with slogans such as “PROMOTE HOMOSEXUALITY. GENERIC QUEER. FAGGOT. MILITANT DYKE.” Wearing these T-shirts, they entered heterosexual bars in New York and San Francisco and staged “kiss-ins.” They visited suburban shopping malls outside these same cities and chanted, “We’re here, we’re queer, we’re fabulous – and we’re not going shopping!” Through these tactics, they not only came out, but forced heterosexuals to acknowledge their presence.

Related | The Oldest Gays in History

The politics of coming out has helped make LGBTQ people more visible and better protected by law. As testimony of this shift, today, marriage equality is the law of the land, the popular TV comedy “Modern Family” features a gay couple and one of the leading candidates for the Democratic presidential ticket, Pete Buttigieg, is a gay man.

To be sure, homophobia and transphobia are still alive and well. Still, LGBTQ people have made clear strides in the past half-century and coming out politics has been part of their success.

Going bigger

The success of the LGBTQ movement has inspired other social movements – such as the fat acceptance movement and the undocumented youth movement, among others – to also “come out.”

As I show in my new book, coming out has become what sociologists call a “master frame,” a way of understanding the world that is elastic and inclusive enough for a wide range of social movements to use.

For example, just as Harvey Milk urged queer people to come out for “youngsters who are becoming scared,” so too the undocumented immigrant youth movement has urged undocumented youth to “come out as undocumented and unafraid.”

Related | A Brief History of Hawaii’s Ancient Gay Culture

As one of the immigrant youth movement leaders quoted in my new book explained, Milk’s speech had impressed upon her and her peers that, “If you don’t come out nobody’s gonna know that you’re there. … They’re gonna say or do whatever they want because nobody’s standing up, and you’re not standing up for yourself.”

This campaign has been effective at convincing undocumented youth to be visible, which has been crucial for political mobilization.

The specific language of “coming out, which is so closely associated with LGBTQ rights, allows other social movements to liken their experience to that of LGBTQ people.

For instance, when fat liberation activist Marilyn Wann speaks about how she “came out” as fat, she is not just speaking about a turning point in her personal biography. By using the term “coming out,” she implies that being fat is like being gay – and that, just as homophobia is morally wrong, so too is “fatphobia.” In this context, coming out as fat means owning one’s fatness and refusing to apologize for it.

As my book shows, the multiple meanings of coming out – including coming into community, cultivating self-love, and collectively organizing to promote equality and justice – offer a productive way for social movements to move forward.

Abigail C. Saguy is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.